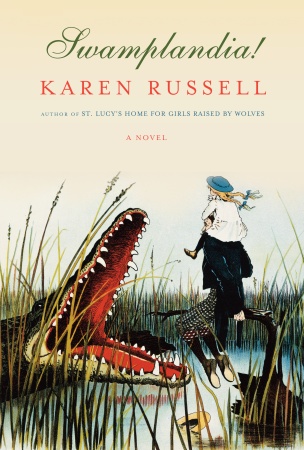

I recently read Karen Russell’s new (first) novel Swamplandia! Karen has been anthologized in the New York Times 20 under 40 as a writer to watch, and with her first story collection titled St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, her new novel featuring an alligator wrestling family in the swamps of the Florida Everglades, her astonishing control of rococo prose, her age around the same as mine–I find I watch her wishing her words were my own. This isn’t a bad envy, though, (I’m eagerly waiting for her short story collection to land in my mailbox) rather it’s the sort of envy that inspires. In her opening to Swamplandia! she writes:

“Nights in the swamp were dark and star-lepered–our island was thirty-odd miles off the grid of mainland lights–and although your naked eye could easily find the ball of Venus and the sapphire hairs of the Pleiades, our mother’s body was just lines, a smudge against the palm trees. Somewhere directly below Hilioa Bigtree, dozens of alligators pushed their icicle overbites and the awesome diamonds of their heads through over three hundred thousand gallons of filtered water.”

Despite being pulled in and delighted by the prose of the story I did find myself asking a few questions: why does Ossie’s ghost-boyfriend Louis Thanksgiving get a whole huge chapter when Ossie herself is never pulled open (as her siblings Ava and Kiwi are)? is the Bird-man right for the story? (I ask that one because when I reached his chapter everything else felt like a beautiful lead-up.) Kiwi’s section is great, and I admire how Karen blended third person into a very first person story, but is it overdone? (I felt myself impatient with the huge whale and the flying gig)

I think the problems are that (at least) two of these chapters were written and published as short stories first: Louis Thanksgiving’s chapter and Ava and the Birdman. I have only read Louis’s short story (waiting on the other to arrive in the mail, as I said) but empathize with Karen not wanting to take the backspace key to any of that prose. I’m guessing the Birdman section suffered a similar what-to-keep problem when it slid into the novel. I suppose that that is the danger of baroque prose–more is more, but more doesn’t fix little structural problems.

This is a beautiful, creative, and tender read by an author with obvious talent.